For Cooper, the future of cancer research lies at the intersection of numbers and biology. At just 22, he’s diving into one of the most exciting and challenging areas of modern science: computational biology, the art and science of analysing large-scale biological and clinical data to unlock insights that can transform patient care. This field is the perfect intersection of his passions: mathematics, statistics and biology, brought together to tackle real-world medical problems.

One of the biggest challenges in cancer research today is understanding how cancer cells interact within organs of the body and how those interactions influence treatment outcomes. Cooper’s research zeroes in on lung cancer, a disease that’s responsible for the most number of cancer deaths globally, and increasingly in non-smokers and younger individuals. By characterising how and where cancer cells interact, not just with themselves but with the body’s immune cells, Cooper aims to identify which factors are most critical for predicting how a patient will respond to therapy.

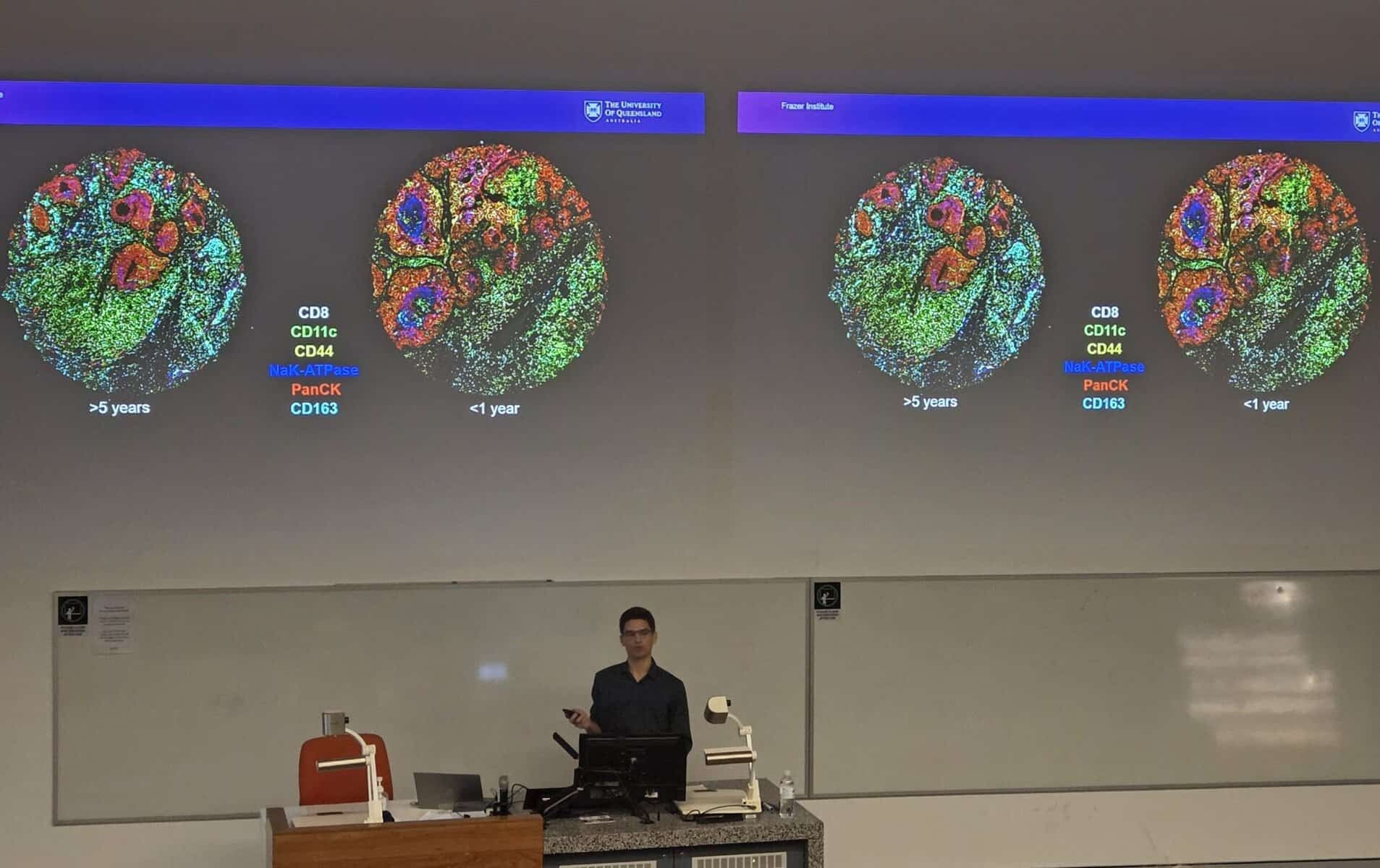

To achieve this, Cooper is leveraging spatial biology, a cutting-edge approach that maps the complex relationships between cancer cells and their surrounding microenvironment. His work, supported by the Wesley Research Institute and in collaboration with the University of Queensland, could pave the way for personalised treatments, offering hope for patients facing lung cancer.

Cooper’s studies were made possible in part through the generosity of the Brazil Family Foundation via Wesley Research Institute. We are deeply grateful for their continued support.

We caught up with Cooper to explore his academic journey and what’s next in his research.

Tell us about your life/experience at university?

I began a dual degree in Mathematics and Science at the University of Queensland (UQ) in 2021, majoring in statistics and genetics. This combination exposed me to two very different sides of science: the quantitative rigour of data analysis and the intricate complexity of biology. The extended program gave me the opportunity to complete two summer research projects, one statistical and one biological, which introduced me to the world of research. During this time, I also secured my first research role, writing code to simulate how animal traits, such as jaw size, evolve over time.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I undertook an Honours, supervised by Associate Professor Arutha Kulasinghe, Dr Aaron Kilgallon and Dr Meg Donovan from the Queensland Spatial Biology Centre (QSBC). This project challenged me to integrate skills from both degrees to deliver clinically relevant insights aimed at improving patient outcomes.

The field of computational biology, or Bioinformatics allows me to combine my passion for mathematics and biology to conduct medically relevant research aimed at improving patient outcomes.

How would you explain your research to someone with no science background?

Cancer is one of the most complex systems in biology, and more work is still needed to develop effective treatment strategies. One major challenge is understanding how cancer interacts with the body and how these interactions influence response to current and emerging treatment options. My research focuses on describing these interactions in lung cancer. By characterising cancer–cancer cell, cancer-immune cell and immune-immune interactions, we can identify which communities and neighbourhoods of cells are most important for predicting patient outcomes such as response to therapy or long term survival.

How does your work connect to real-world issues or applications?

Lung cancer remains a major health burden with very poor treatment outcomes, with only about 25% of patients surviving beyond five years. While new treatments have shown remarkable effectiveness in a subset of patients, we still lack accurate strategies to identify these patients. My Honours project leveraged the wealth of information in spatial biology to uncover cancer cell interactions that are clinically relevant. This knowledge could inform future patient screening and diagnostic approaches, helping determine the most appropriate treatment for each individual.

What methods or tools do you use most often?

I work with data generated from advanced spatial profiling technologies of lung cancers from early to late stages of the disease and investigate how the structural organisation of cancer influences a patient’s response to treatment. The sheer size of these datasets (sometimes reaching terabytes) requires high-performance computing systems just to store and process the data. I use programming languages such as Python and R to develop novel methods for describing cancer structure, which helps inform on how these cells communicate, grow and spread in a patient’s body. This information can be crucial when we’re trying to identify patterns associated with therapeutic benefit and resistance to treatment

How is WRI helping you in your studies? What does it mean to you that we support your honours program?

Receiving the Wesley Research Institute’s scholarship support was a dream come true, as it allowed me to focus fully on my Honours project while remaining financially supported. I also received invaluable guidance from team members at both the WRI and Frazer Institute, including Rafael Tubelleza, Dr Kidane Siele, Dr Clara Lawler and Dr James Monkman. The expertise and advanced technologies have enabled me to explore the critical question of how we can improve patient outcomes, while also helping me develop both my professional and academic skills as a researcher.

What made you interested in this field/area?

Years ago, I first learned why red–green colour blindness is more common in males than females. I was fascinated that such a small genetic change could have such a profound impact on someone’s life, and that curiosity sparked my interest in biology. The sheer complexity of a biological organism is astounding, and understanding even a tiny part can take years of work. We’ve become quite good at understanding what is happening biologically, but often we couldn’t tell where it was happening. It’s like having all the parts of a car and knowing what they do, but not knowing how they fit together. We could guess, but that’s all it would be, a guess.

With spatial biology, however, we can determine both where and what, helping us understand how these systems work. The datasets generated by spatial biology are massive, capturing an enormous amount of information. We’re not yet completely certain how to analyse them, and that’s where budding data scientists like me come in. Finding ways to analyse this data is a challenge that draws on multiple fields, from cell biology to image analysis. The field is rapidly evolving, requiring novel approaches and collaboration to uncover clinically relevant insights.

What’s one misconception people have about your field?

Computational Biology is not always smooth sailing! We constantly face challenges in data analysis due to both computational and biological complexities. One of the most important skills in this field is the ability to identify what went wrong and determine how to fix it. Collaborating with a large and diverse team of computational and biological researchers is invaluable, as it provides access to domain experts who can guide and support us in solving these problems. I have been privileged to work at this interface of biology and big data with mentors who have made me question the status quo and help better my science.

What would you like to do in the future?

I am currently working as a research assistant in the Clinical-omx Lab, where I help streamline the data analysis pipelines, while preparing to begin my PhD next year. I have developed a strong interest in understanding how cancer changes during a patient’s treatment and how this knowledge can be used to improve patient outcomes. Looking further ahead, I aspire to work in translational research, bridging cutting-edge discoveries and emerging technologies into practical, real-world solutions for cancer patients.

As Cooper accelerates into his PhD this year, we’re excited to see the incredible progress he’ll make, not only in his own research journey but also in advancing the fields of spatial and computational biology.